When a patient takes a generic drug and suddenly feels worse-dizzy, nauseous, or worse-most people assume it’s just a side effect. But what if it’s not? What if the generic version, though chemically identical on paper, is triggering a reaction no one expected? That’s where pharmacists come in. Not as afterthoughts. Not as dispensers. But as the frontline defenders of patient safety.

Why Generic Medications Need Extra Attention

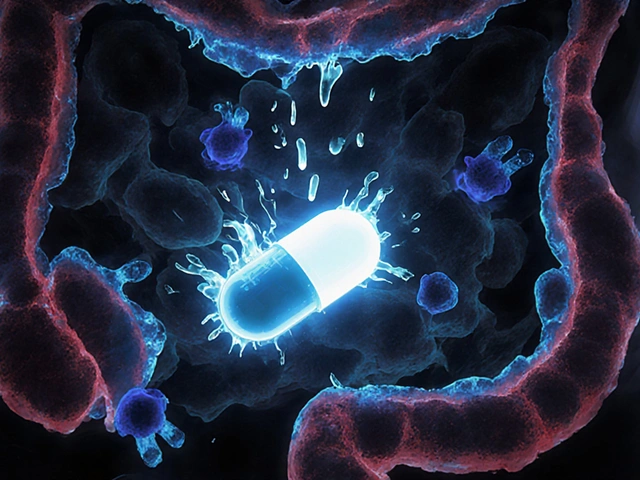

Generic drugs are supposed to be safe copies of brand-name medicines. They contain the same active ingredient, same dose, same route of administration. That’s the law. But safety isn’t just about chemistry. It’s about what’s in the pill besides the active drug-the fillers, dyes, preservatives. These are called excipients. And they’re not always the same between brands and generics. A patient might have taken the brand-name version for years without issue. Then they switch to the generic. Suddenly, they get a rash. Or their blood pressure spikes. Or they feel like they’re floating. These aren’t just "side effects." They’re potential adverse drug reactions (ADRs). And pharmacists are often the first-and sometimes the only-person to connect the dots. The FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) has over 24 million reports since 1968. But experts estimate less than 1% of actual adverse events are ever reported. For generics, the number is even lower. Why? Because everyone assumes they’re identical. That assumption kills vigilance.What Pharmacists Are Legally Required to Do

In some places, reporting isn’t optional. It’s part of the job. In British Columbia, the law is clear: if a pharmacist identifies an adverse reaction, they must notify the prescriber, update the PharmaNet record, and report it to Health Canada. No wiggle room. No "I’ll get to it later." In New Jersey, consultant pharmacists must document adverse reactions and medication errors in the patient’s medical record before the end of their shift. And they must report to the FDA’s system through ASHSP-USP-FDA guidelines. In most other U.S. states? Federal law doesn’t force pharmacists to report. But the FDA strongly encourages it-especially for serious reactions. That means: if the reaction caused hospitalization, led to permanent disability, was life-threatening, or could have killed the patient, it must be reported. And pharmacists are expected to know the difference. It’s not about being a cop. It’s about being a clinician. Pharmacists understand how drugs work. They know which ones interact. They’ve seen what happens when a patient takes five meds at once. That’s why they’re uniquely positioned to spot a pattern others miss.The Real Barrier: Time and Awareness

Here’s the truth: most pharmacists want to report. But they’re stretched thin. A 2021 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 78% of pharmacists spend 15 to 30 minutes per adverse event report. That’s not just filling out a form. It’s talking to the patient, reviewing their history, checking for interactions, documenting everything accurately. And most pharmacies don’t build that time into the schedule. Add to that: many pharmacists don’t even know what counts as reportable. Is a headache after starting a new generic a reaction? Or just a common side effect? What if the patient says, "I feel weird, but I’m not sure why?" Do you report it? The answer is yes-if it’s unexpected, and you suspect the medication. The British Columbia Pharmacists Association calls under-reporting a "recognized problem." And they’re right. When reports don’t come in, regulators can’t see the patterns. They can’t issue warnings. They can’t pull dangerous products. And patients keep getting hurt.

How to Report: Simple Steps

You don’t need a PhD to report. Here’s how to do it right:- Recognize the sign. Any new, unexpected symptom after starting or switching a generic drug. Even if it seems minor. Nausea. Fatigue. Mood changes. Skin rash. Heart palpitations.

- Talk to the patient. Ask: "When did this start?" "Did anything else change?" "Have you taken this before?" Document their exact words.

- Check the record. Look at their medication history. Are they on other drugs that could interact? Did they switch generics recently?

- Decide if it’s reportable. Is it serious? (Hospitalization, life-threatening, permanent harm?) If yes, report immediately. If not, but it’s unexpected, report anyway. The FDA wants to know about all unusual reactions.

- Submit the report. Use MedWatch Online (FDA’s portal). It takes 10 minutes. You can report directly as a healthcare professional. No manufacturer needed.

Why Reporting Matters More for Generics

Dr. Michael Cohen from the Institute for Safe Medication Practices says it best: "When patients experience unexpected reactions to generics, pharmacists are often the first to recognize potential bioequivalence issues or excipient-related problems." A 2022 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that pharmacist-led reporting increased documentation by 37% in community pharmacies. But only 28% of pharmacists reported non-serious-but still unusual-reactions. That’s the gap. Generic manufacturers aren’t required to test every batch for patient-specific reactions. They only need to prove bioequivalence in a small group of healthy adults. That’s not the same as real-world use. An elderly patient with kidney disease. A diabetic on multiple meds. A teenager with allergies. Those patients aren’t in the trials. But they’re taking the generics. And they’re the ones getting hurt. Every report you file adds a piece to the puzzle. One report? Might look like a coincidence. Ten? Might be a trend. A hundred? Might be a recall.

What’s Changing-and What’s Coming

The tide is turning. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative is now pulling data from community pharmacies to monitor safety in real time. California and Texas have integrated reporting tools into pharmacy software, cutting reporting time by 40%. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy is pushing for nationwide integration. Europe made reporting mandatory for all healthcare professionals in 2012. Result? A 220% jump in reports. Now, North America is watching. By 2025, experts predict 75% of U.S. states will follow British Columbia’s lead and make reporting a legal duty-not just a recommendation. That’s not just policy. That’s protection. For patients. For pharmacists. For the whole system.What You Can Do Today

You don’t have to wait for the law to change. Start now. - Know your state’s rules. Even if reporting isn’t mandatory, your board may expect it. - Train your staff. Make sure every pharmacy tech knows what an ADR looks like and where to find the reporting form. - Keep a log. Even if you don’t report every time, track the reactions you see. Patterns emerge over time. - Speak up. If your pharmacy won’t give you time to report, say so. Patient safety isn’t optional. You didn’t go to school for years just to hand out pills. You became a pharmacist to protect people. Reporting adverse events isn’t paperwork. It’s practice.Frequently Asked Questions

Do pharmacists have to report adverse events from generic drugs?

In some states like British Columbia, yes-it’s legally required. In most U.S. states, it’s not mandatory by federal law, but the FDA strongly encourages reporting, especially for serious reactions. Even if not required, pharmacists are ethically and clinically expected to report any suspected adverse drug reaction linked to a generic medication.

What counts as a reportable adverse event?

Serious adverse events include those that cause hospitalization, death, life-threatening conditions, permanent disability, congenital malformations, or require medical intervention to prevent harm. But even non-serious, unexpected reactions-like unusual fatigue, rash, or mood changes after switching to a generic-should be reported. The FDA wants to know about anything unusual, not just the worst cases.

How long does it take to report an adverse event?

Using the FDA’s MedWatch Online portal, a complete report takes about 10 to 15 minutes. This includes gathering patient details, describing the reaction, and confirming the medication involved. Many pharmacists report spending 15-30 minutes total when factoring in patient interviews and documentation.

Why are generic drugs under-reported in adverse event systems?

Many assume generics are identical to brand-name drugs, so unexpected reactions are dismissed as "side effects" rather than potential safety signals. Pharmacists may also lack time, training, or awareness about reporting requirements. Studies show only 5-10% of all adverse reactions are reported, with generics likely reported even less frequently due to this assumption.

Can I report an adverse event if I’m not sure it’s caused by the drug?

Yes. The FDA encourages reporting even when causation isn’t certain. The system is designed to detect patterns over time. One unclear report might seem insignificant, but if 20 other pharmacists report the same reaction with the same generic, it becomes a red flag. Your report could be the first clue in a larger safety issue.

James Rayner

December 15, 2025 AT 20:23Man, I’ve seen this so many times… patient switches to generic, says they feel "off," and everyone just shrugs. But it’s not just "side effects"-it’s the fillers. Dyes. Corn starch. Lactose. I had a guy with a corn allergy get hives after switching to a generic metformin. No one thought to ask about excipients. We’re not just pharmacists. We’re detectives with stethoscopes.

And yeah, the FDA’s system is a nightmare to use. But if you don’t report, how do they know? One report? Maybe noise. Ten? That’s a pattern. A hundred? That’s a recall waiting to happen. I’ve filed 17 reports in two years. Two led to manufacturer changes. That’s worth 10 minutes.

Cassandra Collins

December 17, 2025 AT 12:31Okay but what if the generics are being DOCTORED? Like… I read this one article that said the FDA lets Chinese labs fill the capsules and they’re using talc that’s laced with heavy metals. And the brand names? They’re all just repackaged generics anyway. The whole system is a scam. They don’t want you to know. That’s why they make reporting so hard. It’s not about safety-it’s about profit.

Dave Alponvyr

December 19, 2025 AT 05:3510 minutes. That’s all it takes. You’re not saving the world. You’re just doing your job. Stop acting like you’re a superhero. If your pharmacy won’t give you time, quit complaining. Find a place that respects you. Or don’t report. But don’t act like you’re the only one who sees the problem.

Aditya Kumar

December 19, 2025 AT 23:04Who has time for this? I’m doing 120 scripts an hour. I don’t even have time to say hi to the customers. Report? Nah. I’ll just tell them to call their doctor. That’s not my job.

Joanna Ebizie

December 20, 2025 AT 17:55Ugh. I can’t believe you guys are still talking about this. Like, really? You think the FDA cares? They’re paid off by Big Pharma. The generics are all the same. Stop overthinking. Your patient just has anxiety. Or they’re not taking it right. Or they’re just weird. Stop making everything a crisis.

Elizabeth Bauman

December 21, 2025 AT 14:45As an American, I’m sick of hearing how other countries do it better. Canada? Europe? They’re all socialist messes. We have the best healthcare system in the world. If your patient has a reaction, it’s probably because they’re not eating right or they’re on some herbal nonsense. Stop blaming the system. Take personal responsibility.

Dylan Smith

December 22, 2025 AT 00:07I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately. I used to think reporting was just bureaucracy. But then I saw a woman who had migraines every time she got her generic lisinopril. She’d been on it for 3 years. Switched generics last month. Boom. Headaches. I checked her med history. No new meds. No lifestyle changes. Just the pill. I reported it. Two weeks later, another pharmacist at a different store reported the same thing. Same batch. Same excipient. Now the FDA is looking into it. One report doesn’t mean much. But ten? That’s a voice.

Kitty Price

December 23, 2025 AT 14:03This is so important. I’ve had patients cry because they felt like they were "losing themselves" after switching generics. Not depression. Not anxiety. Just… different. Like their brain didn’t feel like theirs anymore. I never knew what to say. Now I know: it’s not in their head. It’s in the pill. And we’re the only ones who can say it out loud. Thank you for writing this.

sue spark

December 25, 2025 AT 11:59I just started as a pharmacy tech and this changed everything for me. I used to think reporting was for doctors. Now I know it’s for us. I’ve already flagged three weird reactions this week. Not serious. Just odd. But I wrote them down. One day, maybe they’ll matter. I’m proud to be part of this

Ron Williams

December 27, 2025 AT 11:30For those of you in the Midwest or rural areas-this isn’t just policy. It’s survival. I’ve seen patients drive 90 minutes for their meds. They don’t have access to specialists. They don’t have time to chase down doctors. If the pharmacist doesn’t speak up, no one will. That’s not a burden. That’s a calling.

Colleen Bigelow

December 28, 2025 AT 16:59Let’s be real. The FDA is a puppet of the pharmaceutical industry. They know generics are dangerous. They know excipients are unregulated. They know foreign labs cut corners. But they won’t say it. Why? Because if they admit one generic is unsafe, they have to recall them all. And that would cost billions. So they let patients suffer. And they call it "acceptable risk." That’s not science. That’s corporate murder.

Mike Smith

December 29, 2025 AT 18:57As a clinical pharmacist with 22 years in community practice, I can say with absolute certainty: the most underutilized resource in healthcare is the pharmacist’s clinical judgment. We are not technicians. We are not order-fillers. We are the final safety net. Reporting adverse events is not an add-on. It is a core competency. If your institution does not support this, it is failing its patients-and you.

Josias Ariel Mahlangu

December 30, 2025 AT 16:31You people are pathetic. You’re not pharmacists. You’re glorified cashiers. You think reporting some vague feeling means you’re doing something noble? Wake up. The patient took the pill. They’re responsible. If they can’t handle a little nausea, they shouldn’t be on medication. Stop playing doctor. Do your job. Dispense. Don’t diagnose. Don’t report. Just hand out pills and shut up.

Billy Poling

December 30, 2025 AT 19:30It is imperative to acknowledge, in the most rigorous and academically sound manner possible, that the structural and systemic underreporting of adverse drug events-particularly those associated with generic pharmaceutical formulations-is not merely a function of individual negligence or institutional inertia, but rather a deeply entrenched epistemological failure within the pharmacovigilance ecosystem, wherein the epistemic authority of the regulatory apparatus is predicated upon an ontological assumption of bioequivalence that is, in fact, empirically untenable when subjected to the heterogeneity of real-world patient populations, particularly those with polypharmacy, age-related metabolic decline, and genetic polymorphisms affecting drug metabolism, which are categorically excluded from the bioequivalence trials mandated under the Hatch-Waxman Act, thereby creating a profound and dangerous disconnect between regulatory compliance and clinical reality, and thus, the moral imperative to report-even in the absence of legal mandate-becomes not merely an ethical obligation, but a necessary act of epistemic resistance against the commodification of human health under neoliberal healthcare paradigms.