The Orange Book database is the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s official list of prescription drugs approved for sale in America - but it’s not just a catalog. It’s a legal roadmap that determines when generic drugs can enter the market, how much patients pay, and even whether a pharmacist can swap a brand-name pill for a cheaper version without asking a doctor.

What the Orange Book Actually Contains

The full name is Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. It sounds bureaucratic, but it’s simple in purpose: it tells you which drugs the FDA says work the same way, and which patents block generics from being sold.

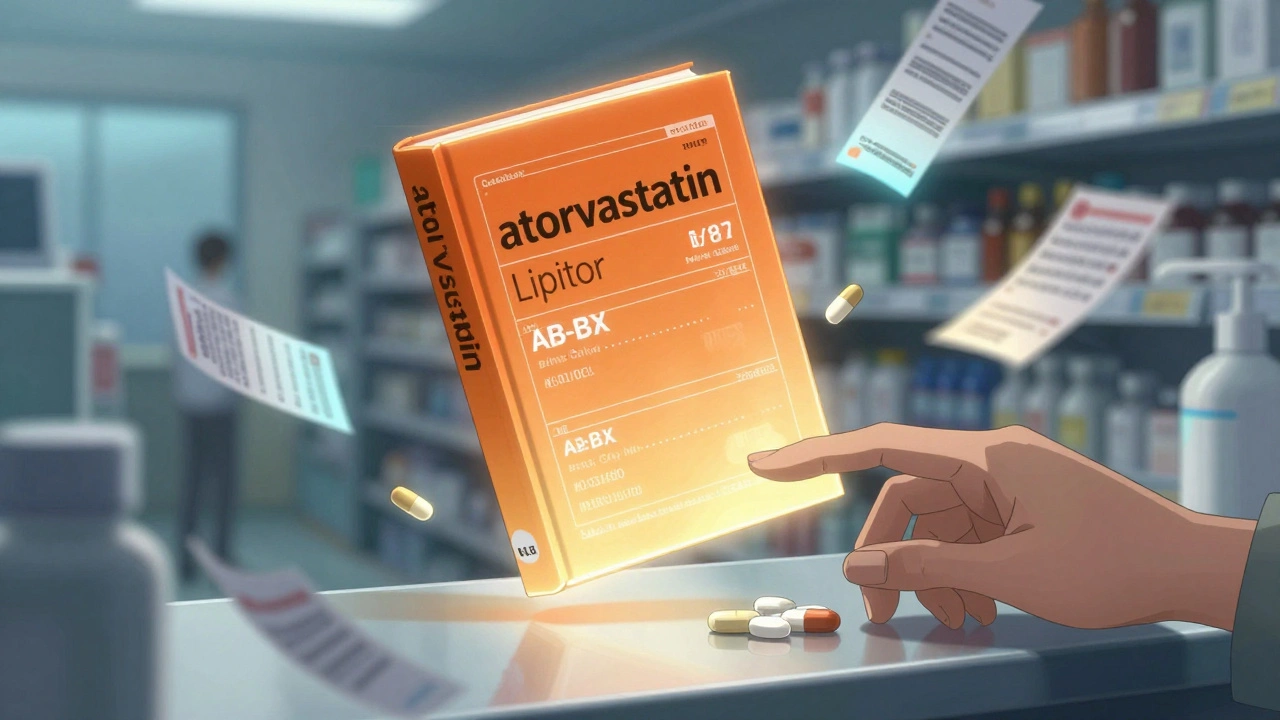

Every entry includes the brand name (like Lipitor), the generic name (atorvastatin), the dosage form (tablet, capsule, injection), strength, and the application number - either an NDA for the original brand or an ANDA for the generic copy. But the real power lies in two hidden layers: patents and exclusivity.

Patents listed here aren’t just any patents. They’re the ones the brand company was legally required to submit within 30 days of approval. Each patent has an expiration date and a use code - a letter like A, B, or C - that tells you which medical condition it covers. For example, a patent might cover using a drug for high blood pressure but not for heart failure. That’s critical for generics: if they can prove their product doesn’t infringe on the protected use, they can launch sooner.

Then there’s regulatory exclusivity. This isn’t a patent. It’s a legal shield the FDA gives to reward innovation. A new chemical entity gets five years of market protection. If a drug treats a rare disease, it gets seven years. If a company tests it in kids, they get an extra six months. These dates are just as important as patent expirations. A generic manufacturer can’t legally enter until both the patent and exclusivity have expired.

Why It Matters for Generic Drugs

Before 1984, bringing a generic drug to market was a nightmare. Companies had to run full clinical trials - the same expensive, time-consuming tests as the original brand. That made generics rare and expensive.

The Hatch-Waxman Act changed everything. It created the ANDA pathway: generics no longer needed to prove safety and effectiveness again. Instead, they had to prove they were bioequivalent - meaning they delivered the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate.

But here’s the catch: they had to certify against every patent listed in the Orange Book. They could say: “We’re not infringing,” “We think this patent is invalid,” or “We’ll wait until it expires.” That certification process is the legal trigger that starts the clock on generic competition.

The Orange Book makes this possible. Without it, generics wouldn’t know which patents to challenge or when to file. Today, 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. That’s $1.68 trillion in savings since 1984 - and the Orange Book is the reason.

Therapeutic Equivalence Ratings: AB, BX, and What They Mean

Not all generics are created equal - at least not in the eyes of the FDA. The Orange Book assigns each drug a therapeutic equivalence rating. The most common? AB.

AB means the generic is therapeutically equivalent to the brand. It’s bioequivalent, it’s manufactured under the same quality standards, and pharmacists can substitute it without consulting the prescriber. In most states, that’s automatic.

Then there’s BX. That’s a red flag. It means the FDA doesn’t have enough data to say the generic is interchangeable. Maybe the drug has a narrow therapeutic index - where tiny differences in dosage can cause harm. Think warfarin or thyroid meds. Pharmacists can’t swap these without the doctor’s OK.

Pharmacists check this rating every day. One hospital pharmacist in Ohio told me: “When a doctor writes ‘Lipitor’ on the script, I pull up the Orange Book. If it’s AB-rated, I call and say, ‘We can save you $120 a month - is that OK?’” That’s not just cost-saving. It’s better care.

Who Uses the Orange Book - And How

It’s not just for lawyers and drug companies. Here’s who relies on it daily:

- Generic manufacturers - Their legal teams monitor the database every morning. When a patent expires, they file ANDAs within hours. Some have automated alerts.

- Pharmacists - They use it to verify substitution rules and avoid liability. One study found 92% of hospital pharmacists consult it regularly.

- Doctors - Increasingly, they check it when prescribing. If a patient can’t afford a brand, they look up the AB-rated generic.

- Patients - More than 1.2 million people visit the public site monthly. They search for cheaper options or check why their generic wasn’t filled.

Even researchers use it. The National Bureau of Economic Research built a public dataset from the Orange Book. Since 2020, 78% of pharmaceutical economics papers have used it to study how patent strategies affect drug prices.

Where the System Breaks Down

For all its power, the Orange Book isn’t perfect. The biggest criticism? “Evergreening.”

Some brand companies file patents on tiny changes - like a new coating, a different pill shape, or a slightly altered release mechanism - just to reset the clock. These patents often have weak legal standing. But they still show up in the Orange Book, scaring off generics.

In 2021, Harvard’s Aaron Kesselheim told Congress: “The Orange Book has become a tool for delay, not competition.” The Congressional Research Service confirmed it: over 40% of patents listed in recent years were challenged in court and later found invalid.

Another problem: delays. If a patent dispute ends in a settlement, it can take weeks - sometimes months - for the FDA to update the database. During that time, generics sit idle. One company lost $80 million in potential sales because the settlement wasn’t reflected in time.

And then there’s the lack of transparency in patent use codes. Over a third of users say they don’t understand what the letters mean. The FDA offers a guide, but it’s dense. You need training to decode it.

What’s Changing in 2025

The FDA is finally updating the system. In January 2024, they proposed new rules:

- Patents must be tied to specific approved uses - no more vague, broad claims.

- Updates to the database must happen within 48 hours of a patent change or court ruling.

- Manufacturers must explain why a patent is relevant - not just list it.

They’re also launching a full public API by the end of 2024. Developers will be able to build apps that pull real-time data - imagine a browser extension that shows you generic alternatives as you shop for prescriptions.

Why does this matter? Because $157 billion in branded drugs are set to lose patent protection by 2028. If the Orange Book works as it should, those drugs could become generic within weeks - not years. That could save the U.S. healthcare system $420 billion over the next five years.

How to Use It Yourself

You don’t need a law degree to use the Electronic Orange Book. Go to accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/. Search by brand name, generic name, or active ingredient.

Look for:

- The therapeutic equivalence rating (AB = safe to substitute)

- Patent expiration dates (watch for the ones marked "patent expired")

- Exclusivity end dates (these are often later than patents)

Most people find what they need in under five minutes. If you’re confused, the FDA offers free video tutorials. They’re not flashy, but they’re clear.

The Bigger Picture

The Orange Book isn’t just a database. It’s a balance - between innovation and access, between profit and public health. It lets companies protect their research, but only for a limited time. It lets generics compete, but only if they play by the rules.

And it works. The average time from patent expiration to generic entry has dropped from 36 months in 1990 to just 11 months today. That’s because of transparency. That’s because of the Orange Book.

It’s not perfect. It’s not easy. But for patients paying out-of-pocket for insulin, blood thinners, or cholesterol meds - it’s the reason they can afford to live.

Shayne Smith

December 6, 2025 AT 13:55Just checked my last prescription - switched to the generic and saved $90. The Orange Book made it stupid easy. Pharmacists are the real MVPs here.

Max Manoles

December 6, 2025 AT 15:59The Orange Book is one of the most underappreciated public health tools in American medicine. It’s not glamorous, but without it, the entire generic drug ecosystem collapses. The patent-use codes? Messy. The therapeutic equivalence ratings? Crystal clear. The FDA’s proposed 48-hour update rule? Long overdue. This isn’t bureaucracy - it’s infrastructure. And infrastructure, when maintained, saves lives.

Annie Gardiner

December 6, 2025 AT 21:27Wow, so the government tells you what medicine you can take? How cozy. I bet they also pick your toothpaste and decide if your coffee is ‘therapeutically equivalent’ to espresso. Next they’ll rate your yoga mat on bioequivalence. I mean, who even *is* the FDA? A bunch of lawyers with clipboards and a love for Latin?

Rashmi Gupta

December 7, 2025 AT 04:48India has its own drug registry - much simpler, no patent games. Why does America need all this? Why not just let generics in immediately? You spend more time reading patents than taking pills.

Kumar Shubhranshu

December 9, 2025 AT 00:23Nigel ntini

December 9, 2025 AT 01:50Love how this post breaks it down without jargon. The AB vs BX distinction? Life-changing for people on warfarin or thyroid meds. And the fact that pharmacists are doing this legwork daily? That’s healthcare done right - quiet, competent, and patient-focused. Kudos to the FDA for finally fixing the delays. It’s about time.

Gwyneth Agnes

December 9, 2025 AT 19:14Ashish Vazirani

December 10, 2025 AT 11:04Mansi Bansal

December 11, 2025 AT 09:14One must acknowledge, with the utmost gravity, that the Orange Book constitutes a veritable epistemic architecture of pharmaceutical governance. The conflation of patent exclusivity with therapeutic equivalence, whilst ostensibly facilitating market competition, inadvertently engenders a hermeneutic labyrinth wherein the layperson - nay, even the clinician - is rendered epistemologically disempowered. The proposed API, though technologically laudable, fails to address the ontological crisis of pharmaceutical transparency. One must ask: Is access to data equivalent to access to justice?

Kay Jolie

December 12, 2025 AT 02:31Look - the Orange Book isn’t just a database, it’s a *paradigm shift* in pharmaceutical epistemology. The AB/BX ratings? That’s not just bioequivalence - it’s a semiotic code for trust in pharmacological ontology. And the patent use codes? They’re not legal artifacts - they’re *narrative thresholds* that determine whether a molecule becomes medicine or a monopoly. The FDA’s API launch? That’s the moment the pharmacovigilance singularity begins. We’re not just talking about savings - we’re talking about the democratization of therapeutic agency. The people are finally getting their data back. And honestly? It’s about damn time.