When an older adult suddenly becomes confused, withdrawn, or agitated, it’s easy to blame aging or dementia. But what if it’s not? In many cases, the real culprit is a medication they started just days before. Medication-induced delirium is one of the most common - and most preventable - causes of sudden mental changes in people over 65. It doesn’t come on slowly. It hits fast. And if you miss it, the consequences can be deadly.

What Exactly Is Medication-Induced Delirium?

Delirium isn’t just being forgetful. It’s a sudden, dramatic shift in thinking, attention, and awareness that can come and go within hours. Someone who was sharp and alert one day might be staring blankly at the wall the next, or worse - yelling at imaginary people, pacing nonstop, or refusing to eat or drink. This isn’t dementia. It’s not depression. It’s medication-induced delirium, and it’s often reversible if caught early.

Unlike dementia, which creeps in over years, delirium appears in hours or days. It’s tied directly to drugs that mess with brain chemistry - especially those that block acetylcholine, a key neurotransmitter for memory and focus. Older adults are especially vulnerable because their brains are less able to handle these chemical disruptions. Even a single new pill can trigger it.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not every older adult gets delirium from medication. But some are far more likely. The biggest risk factors:

- Age 85 or older - they’re more than twice as likely to develop it as those in their late 60s.

- Already living with dementia or Parkinson’s - their brains are already fragile.

- Taking three or more medications with anticholinergic effects - risk jumps nearly fivefold.

- Recently hospitalized or in the ICU - stress, sleep loss, and multiple drugs combine dangerously.

- Dehydrated or malnourished - poor body chemistry makes the brain more sensitive.

Women over 80 with arthritis and urinary issues are especially common cases. They’re often prescribed diphenhydramine (Benadryl) for sleep, oxybutynin for bladder control, and amitriptyline for nerve pain - all high-risk drugs. One after another, they pile up. And then, suddenly, their personality changes.

The Hidden Danger: Hypoactive Delirium

Most people picture delirium as loud, frantic behavior - shouting, hallucinating, thrashing. That’s hyperactive delirium. But in older adults, it’s rarely like that. About 72% of cases are hypoactive - quiet, still, and deeply misleading.

These patients sit quietly in their chairs. They don’t answer questions. They don’t smile. They seem ‘just tired’ or ‘depressed.’ Family members say, ‘She’s always been like this lately.’ But it’s not normal aging. It’s a brain in crisis. And because it’s quiet, it’s missed. Hospital staff often don’t recognize it. In fact, 70% of hypoactive cases go undiagnosed.

That’s why caregivers need to watch for subtle signs: a loved one who no longer recognizes family, stops reading the newspaper, forgets how to use the TV remote, or just stares out the window for hours. These aren’t personality quirks. They’re red flags.

The Top Culprits: Which Medications Cause It?

Not all drugs are equal. Some are far more dangerous for older brains. The biggest offenders fall into three categories:

1. Anticholinergic Drugs

These block acetylcholine - the brain’s signal for memory, attention, and alertness. The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria® lists 56 of these as unsafe for seniors. Common ones include:

- Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) - still sold as a sleep aid, despite being one of the worst offenders.

- Oxybutynin (Ditropan) - for overactive bladder.

- Amitriptyline - an old antidepressant still used for nerve pain.

- Hyoscine (Buscopan) - for stomach cramps.

- Chlorpheniramine - found in many cold and allergy meds.

Each of these has a strong anticholinergic score. When you add even two together, the risk skyrockets. A 2004 study found that people taking three or more of these had a 4.7 times higher chance of delirium.

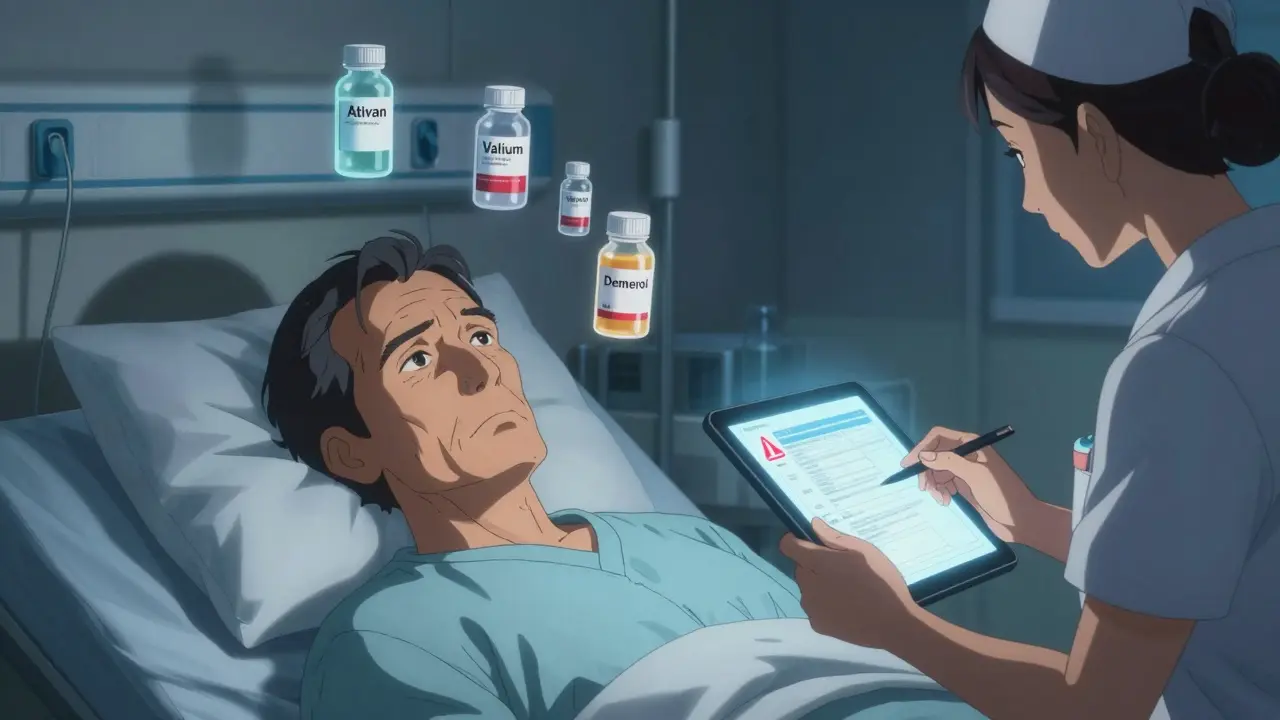

2. Benzodiazepines

Drugs like lorazepam (Ativan), diazepam (Valium), and alprazolam (Xanax) are prescribed for anxiety, insomnia, or seizures. But they slow brain activity too much. Studies show they triple the risk of delirium in hospital settings. Even short-term use - just a few days - can trigger it. And if stopped suddenly, they can cause withdrawal delirium, which is just as dangerous.

Long-acting versions like diazepam are worse. Short-acting ones like lorazepam are slightly safer - but still risky. Experts say they should only be used for alcohol withdrawal, seizures, or end-of-life care.

3. Opioids

Pain meds like morphine and codeine can cause confusion, especially in older adults. But not all opioids are the same. Meperidine (Demerol) is especially dangerous because its metabolite builds up in the brain and causes seizures and hallucinations. Morphine is better than meperidine, but hydromorphone (Dilaudid) has been shown to cause 27% less delirium at the same pain-relieving dose.

For pain, doctors should start with acetaminophen and non-drug methods - ice, heat, physical therapy - before turning to opioids.

How to Prevent It Before It Starts

The best way to handle medication-induced delirium? Don’t let it happen in the first place.

1. Do a Full Med Review - Every Time

Every time an older adult sees a new doctor, gets a new prescription, or is admitted to the hospital, ask: ‘Is this drug really necessary?’

Use the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale (ACB). It rates drugs from 0 (no effect) to 3 (strong effect). A score of 3 or higher means high risk. If someone’s total ACB score is 3 or more, start asking: Can we cut one? Replace it? Try something safer?

For example: Swap diphenhydramine for loratadine (Claritin) - same allergy relief, no brain fog. Swap oxybutynin for mirabegron (Myrbetriq) - better for older bladders. Swap amitriptyline for duloxetine - lower anticholinergic burden.

2. Use STOPP/START Guidelines

This is a proven tool used in hospitals across the UK and US. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) flags bad drugs. START (Screening Tool to Alert Doctors to Right Treatment) suggests what’s missing. A 2018 study showed using this system cut delirium by 26%.

3. Avoid ‘Just in Case’ Prescriptions

Too many seniors get pills ‘just in case’ they get sick. ‘Here’s a sleeping pill, just in case you can’t sleep.’ ‘Here’s an antihistamine, in case you get a cold.’ These aren’t preventive - they’re dangerous. Every new drug is a new risk.

4. Use Non-Drug Alternatives

For sleep: try melatonin, strict bedtime routines, or light therapy.

For pain: use heat wraps, physical therapy, or acupuncture.

For bladder issues: pelvic floor exercises, timed voiding, fluid management.

For anxiety: calming music, gentle walks, pet therapy, or cognitive behavioral techniques.

What to Do If Delirium Happens

If you notice sudden changes, act fast.

- Check for new medications - especially in the last 3-7 days.

- Stop non-essential drugs immediately - especially anticholinergics and benzodiazepines.

- Call the doctor. Don’t wait. Say: ‘I think this is medication-induced delirium.’

- Get basic labs done: sodium, potassium, kidney function, thyroid, vitamin B12, and infection markers.

- Keep the environment calm - reduce noise, keep lights on at night, have familiar objects nearby.

- Don’t sedate. Don’t restrain. Don’t assume it’s ‘just dementia.’

Most cases improve within days once the trigger is removed. But if it’s missed for a week, recovery can take months - or never happen.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

This isn’t just about one person’s confusion. It’s about cost, care, and survival.

People with delirium stay in the hospital 8 days longer on average. Their risk of dying within a year doubles. Many never regain their independence. And the financial cost? Over $164 billion a year in the U.S. alone.

Worse, hospitals are now penalized for it. Since 2018, Medicare doesn’t pay for complications from delirium - they call it a ‘never event.’ That means hospitals are finally being forced to pay attention.

Some are using AI tools that scan electronic records and flag high-risk drug combinations before they’re even prescribed. Others train nurses to spot hypoactive delirium using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). Hospitals that do this see 32% fewer cases.

But most still don’t. A 2023 study found 43% of U.S. hospitals still routinely give high-risk drugs to older patients. Only 18% check anticholinergic burden at all.

What Families Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to be a doctor to protect someone you love.

- Keep a written list of every medication - including over-the-counter pills and supplements.

- Ask every prescriber: ‘Is this drug safe for someone my age?’

- Ask: ‘Is there a safer alternative?’

- Watch for sudden changes in behavior, sleep, or speech - even small ones.

- If you suspect delirium, say it out loud: ‘I think this might be from a medication.’

- Don’t let doctors dismiss it as ‘just old age.’

Delirium is not normal. It’s not inevitable. It’s a warning sign - and one that’s almost always fixable.

Final Thought

Medication-induced delirium is the silent crisis in senior care. It’s not rare. It’s not mysterious. It’s predictable. And it’s preventable. We have the tools. We have the science. What we’re missing is the urgency.

Every pill prescribed without thinking carries risk. Every delay in asking ‘Why?’ costs time, health, and sometimes life. The next time you see a loved one change suddenly - don’t assume it’s aging. Ask: ‘What changed in their meds?’

Can over-the-counter meds cause delirium in older adults?

Yes - and they’re often the biggest culprit. Medications like Benadryl (diphenhydramine), cold and flu remedies with antihistamines, and sleep aids with doxylamine are all strong anticholinergics. Many seniors take them daily for allergies or insomnia, not realizing they’re poisoning their brain chemistry. These are not harmless. They’re high-risk.

Is delirium the same as dementia?

No. Dementia is slow, progressive, and usually permanent - it develops over years. Delirium is sudden, fluctuating, and often reversible. Someone with dementia can still have delirium on top of it - and that’s especially dangerous. The two can look similar, but delirium is a medical emergency. Dementia is not.

How long does medication-induced delirium last?

It depends. If the drug is stopped early, symptoms can clear in 2-5 days. But if it’s missed for a week or more, especially in someone with dementia, it can last weeks or months. In some cases, the brain never fully recovers. The longer it goes untreated, the higher the chance of permanent cognitive decline.

Can benzodiazepines be safely used in older adults?

Rarely. They should only be used for alcohol withdrawal, acute seizures, or end-of-life comfort. Even then, short-acting ones like lorazepam are preferred. Long-acting versions like diazepam are dangerous. For anxiety or insomnia, non-drug approaches or safer meds like melatonin or low-dose trazodone are better options.

What should I do if my parent is in the hospital and seems confused?

Ask the nurse or doctor: ‘Could this be delirium?’ Request a full medication review - especially for anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, and opioids. Ask if any new drugs were started in the last 72 hours. Push for the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) screening. Don’t accept ‘it’s just the hospital’ as an answer. Delirium is not normal - even in hospitals.

Are there any new tools to help prevent this?

Yes. Some hospitals now use AI tools that scan electronic health records and flag dangerous drug combinations before they’re prescribed. The FDA now requires stronger warnings on anticholinergic labels. And the National Institute on Aging is funding real-time monitoring systems that alert doctors when a patient’s anticholinergic burden is too high. These aren’t perfect yet - but they’re changing the game.

Jon Paramore

December 21, 2025 AT 22:18Anticholinergic burden scoring is underutilized in primary care. ACB scale >3 should trigger automatic pharmacy review - it’s not optional. The 2019 JAMA study showed 42% reduction in delirium when integrated into EHR alerts. We’re still treating seniors like they’re 40 with a pharmacokinetic profile that’s 80.

Swapneel Mehta

December 23, 2025 AT 14:54This is the kind of post that makes me hopeful. We’ve been taught to accept cognitive decline as inevitable, but the truth is, a lot of it is just bad prescribing. I’ve seen my grandfather bounce back after stopping Benadryl. It’s not magic - it’s medicine.

Dan Adkins

December 25, 2025 AT 05:50It is not merely a matter of pharmacological risk assessment; it is a systemic failure of geriatric education within the American medical establishment. The Beers Criteria have been available since 1991, yet institutional inertia persists. One must question the integrity of prescribing practices when profit-driven pharmaceutical marketing supersedes evidence-based guidelines. The consequences are not merely clinical - they are ethical.

Erika Putri Aldana

December 26, 2025 AT 21:09So basically, doctors are poisoning old people with sleep aids? 🤦♀️ I knew my grandma was acting weird after her new 'allergy pill'... but they just told me she's 'getting old.' Like, thanks for that insight, Dr. Obvious.

Adrian Thompson

December 28, 2025 AT 15:18Who’s funding this? Big Pharma hates this article. They make billions off Benadryl and Ativan. You think hospitals are gonna change because some blog post says so? Nah. They’re still giving 80-year-olds Xanax for 'anxiety' while they wait for a bed. This is all woke medicine - pretend science to make you feel good while the system rots.

Teya Derksen Friesen

December 29, 2025 AT 15:12Every healthcare provider should be required to complete a mandatory module on geriatric pharmacology before prescribing. Non-negotiable. The data is clear. The tools exist. The cost of inaction is measured in lost autonomy, prolonged hospitalization, and preventable death. We owe our elders better.

Jason Silva

December 29, 2025 AT 18:39My uncle was misdiagnosed with dementia for 9 months. Turned out it was oxybutynin + amitriptyline + melatonin (yes, melatonin has anticholinergic effects too, weirdly). Once they pulled the meds? He remembered his wife’s name within 72 hours. 🙏💊 #MedicationSafety

Peggy Adams

December 31, 2025 AT 05:02So let me get this straight - we’re told to take Benadryl for allergies and sleep, but it’s basically brain poison for seniors? And nobody told us? What else are we being fed that’s slowly frying our parents’ brains? 🤔

Sarah Williams

January 2, 2026 AT 04:18My mom’s on two of these. I’m taking her to her PCP next week with a printed ACB score sheet. No more 'just in case' meds. If it’s not helping, it’s hurting. Period.

Theo Newbold

January 3, 2026 AT 04:01Interesting how the article ignores the fact that delirium rates spiked during the pandemic due to ICU overuse and polypharmacy - but no mention of how the CDC’s guidelines encouraged benzodiazepine overuse for sedation. The system is broken, not the drugs.

Jay lawch

January 3, 2026 AT 15:37Let us not delude ourselves into believing this is merely a clinical issue. This is a symptom of a civilization in decline - where efficiency replaces wisdom, where profit eclipses compassion, where the elderly are rendered invisible until they become a liability. The anticholinergic burden is not just a pharmacological metric - it is a moral indictment. We have built a healthcare system that treats aging as a disease to be managed with pills, not a human condition to be honored with presence. The real delirium is not in the minds of the aged - it is in the collective denial of the society that abandons them.

Christina Weber

January 5, 2026 AT 15:33Correction: Melatonin does not have significant anticholinergic activity. It acts on MT1 and MT2 receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. The assertion in Jason Silva’s comment is pharmacologically inaccurate and undermines the credibility of the broader argument. Precision matters - especially when lives are at stake.