Statin Tolerance Risk Calculator

This tool helps determine your risk of statin-induced muscle pain based on your SLCO1B1 genotype and the specific statin you're taking. The SLCO1B1 gene variant significantly affects how your body processes statins, particularly simvastatin.

Millions of people take statins to lower cholesterol and prevent heart attacks, but for a significant number, the pills come with a painful trade-off: muscle pain, weakness, or cramps that make them stop taking them. This isn’t just bad luck - it’s often written in their DNA. Pharmacogenomics testing is now giving doctors a clearer look at why some people can’t tolerate statins, and why others can take them without issue. The key? A single gene variant called SLCO1B1 a gene that controls how the liver absorbs statins from the bloodstream.

Why Some People Can’t Tolerate Statins

Statins work by blocking an enzyme in the liver that makes cholesterol. But they don’t just stay in the liver. When they enter the bloodstream, they can travel to muscles and cause damage. For most people, this is harmless. For others, it leads to muscle pain so severe they quit the medication. This isn’t psychosomatic. It’s biological. And it’s tied to how quickly or slowly their body processes these drugs. The biggest clue came from a 2008 study that found people with a specific version of the SLCO1B1 gene had dramatically higher rates of muscle injury when taking high-dose simvastatin. That version - known as the C allele at position rs4149056 - changes the shape of a protein that shuttles statins into the liver. If that protein doesn’t work right, the statin builds up in the blood and leaks into muscle tissue. The risk isn’t small. People with two copies of the C variant (CC genotype) are over four times more likely to develop severe muscle damage than those with two T variants (TT genotype). Even one copy (TC) raises the risk by more than two-fold.Not All Statins Are Created Equal

This gene variant matters most for simvastatin. That’s why clinical guidelines focus on it. But if you’re taking atorvastatin or rosuvastatin, the same genetic risk doesn’t apply. Studies involving over 11,000 patients found no link between SLCO1B1 variants and muscle symptoms with these two statins. Why? Because they’re handled differently by the body. Simvastatin relies heavily on the SLCO1B1 transporter to get into the liver. Atorvastatin and rosuvastatin use other pathways. So if you had muscle pain on simvastatin, switching to one of these might solve the problem - no genetic test needed. But here’s the catch: not everyone knows which statin they were on when they had side effects. And not all doctors remember to ask. That’s where testing helps. If someone had to stop a statin due to muscle pain, a simple genetic test can tell whether SLCO1B1 was the culprit. If it was, they can avoid simvastatin entirely. If not, the issue might be something else - age, thyroid problems, vitamin D deficiency, or even another medication they’re taking.Other Genes That Play a Role

SLCO1B1 isn’t the whole story. Other genes also influence how statins behave in the body. CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 help break down certain statins. If someone has a slow-metabolizer version of these genes, statins can build up even at low doses. Then there’s ABCB1 and ABCG2 - genes that pump statins out of cells. If these pumps are too active or too weak, it changes how much statin stays in the muscle. More recent studies have pointed to GATM and CACNA1S, genes involved in muscle energy and calcium regulation, as possible contributors. And in 2021, researchers found a strong signal in the SOAT1 gene, which is involved in cholesterol storage. We don’t yet know how it works, but it’s a new piece of the puzzle. Still, SLCO1B1 explains only about 6% of all statin-related muscle symptoms. That means most people who have side effects don’t have this genetic variant. So testing can’t predict everything. But for those who do have it, it can be life-changing.

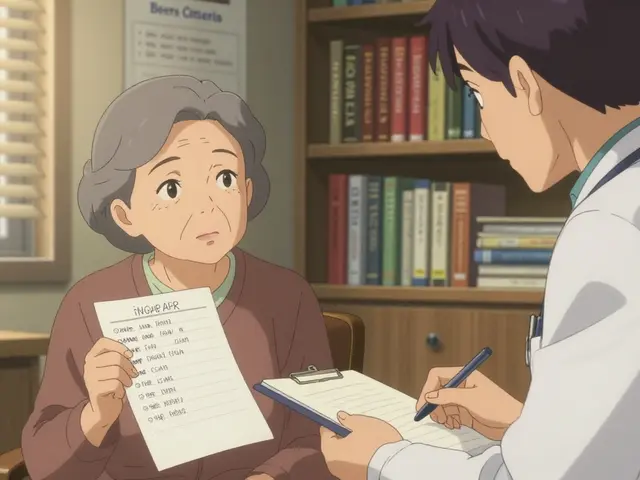

What the Guidelines Say

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) has clear advice: don’t give simvastatin 80 mg to anyone with the CC genotype. For TC carriers, they recommend lower doses or alternative statins. These aren’t vague suggestions - they’re based on clinical data from thousands of patients. Many hospitals now use electronic health records that automatically warn doctors if a patient with the CC genotype is prescribed high-dose simvastatin. Systems like Epic and Cerner can flag these risks in real time. But not all guidelines agree. The American College of Cardiology says testing might be useful if someone is being rechallenged with simvastatin after stopping due to side effects. But they don’t recommend it for everyone starting statins. Why? Because we still don’t have solid proof that testing improves long-term heart outcomes. If someone stops statins because of muscle pain, their risk of heart attack goes up. But does testing prevent that? The evidence is mixed. A 2020 clinical trial found that giving doctors SLCO1B1 results didn’t make patients more likely to stay on statins or report fewer symptoms. That surprised a lot of experts. It suggests that knowing the genetic risk doesn’t always change behavior - either because patients don’t trust the test, or because doctors don’t know how to act on it.Real Stories, Real Results

At Mayo Clinic, 78% of patients who had previously stopped statins due to muscle pain were able to restart a statin successfully after genetic testing guided their choice. One 54-year-old woman had been on simvastatin for years. When her muscles ached so badly she could barely climb stairs, she quit. Her LDL cholesterol jumped from 92 to 168. After testing revealed she had the CC genotype, her doctor switched her to pravastatin. Within six months, her muscle pain vanished. Her LDL dropped back to 92. She’s been on it for over a year and feels better than she has in a decade. But not everyone has that luck. On patient forums, 27% say they still had muscle pain even after switching based on their genes. Some blame the test. Others blame their doctor. A few say they were never given a clear explanation of what the results meant.

Sonja Stoces

February 14, 2026 AT 02:48Kristin Jarecki

February 15, 2026 AT 03:10Vamsi Krishna

February 15, 2026 AT 19:59christian jon

February 16, 2026 AT 05:09Pat Mun

February 16, 2026 AT 22:51Sophia Nelson

February 18, 2026 AT 00:35Steve DESTIVELLE

February 18, 2026 AT 03:08steve sunio

February 18, 2026 AT 14:35Gloria Ricky

February 19, 2026 AT 10:14Stacie Willhite

February 20, 2026 AT 04:27Jason Pascoe

February 22, 2026 AT 03:51Ojus Save

February 22, 2026 AT 09:46Alyssa Williams

February 22, 2026 AT 21:19Reggie McIntyre

February 23, 2026 AT 12:27