When a generic drug company submits an application to the FDA, they’re not just asking for permission to sell a cheaper version of a brand-name drug. They’re asking the FDA to confirm that their product is therapeutically equivalent-same active ingredient, same strength, same route of administration, and most importantly, the same effect in the body. But more than half of these applications don’t pass the first review. Why? Because of deficiency letters.

A deficiency letter isn’t a rejection. It’s a detailed roadmap of what’s missing, wrong, or unclear in your application. The FDA sends these letters when an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) has gaps that prevent approval. These aren’t minor typos or formatting issues. They’re technical, scientific, and often costly mistakes that delay market entry by months-or even years.

What’s Most Often Wrong in Generic Drug Applications?

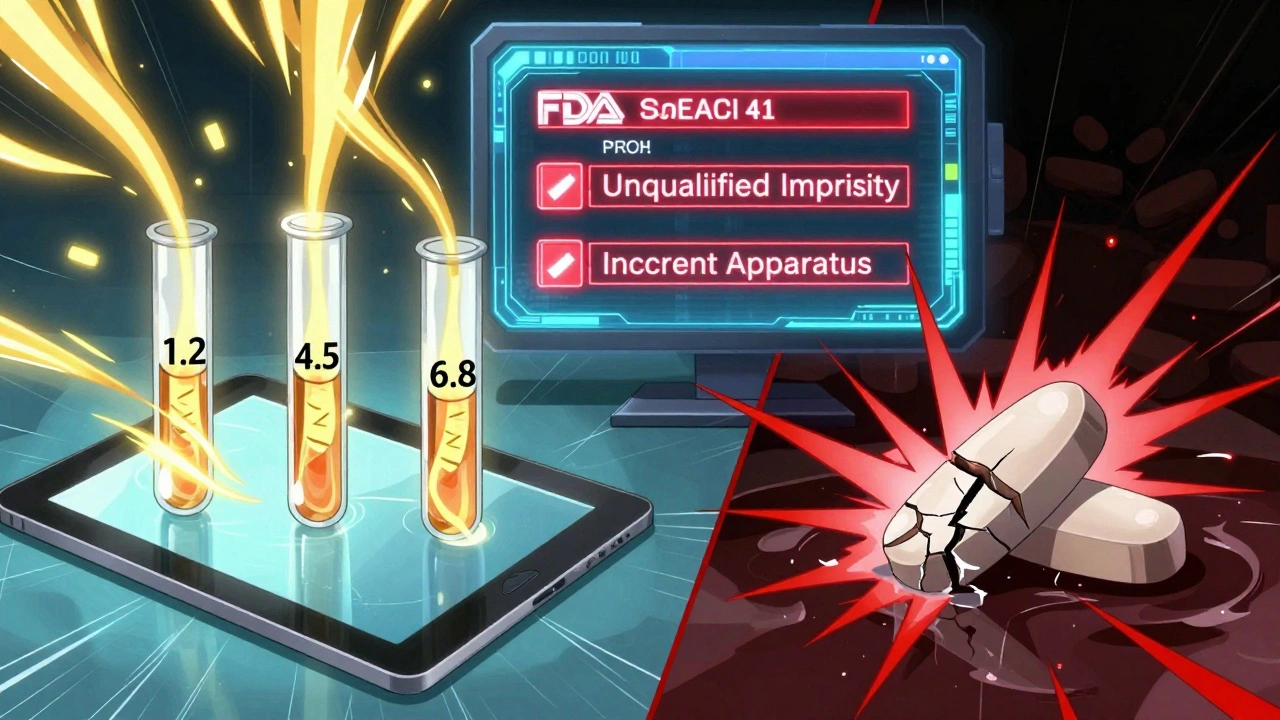

Over 70% of major deficiencies in ANDAs are quality-related. That means the problem isn’t with the science behind the drug’s effect-it’s with how it’s made, tested, or documented. The FDA’s 2024 analysis of submissions from 2018 to 2023 breaks it down clearly:

- Unqualified impurities: 20%

- Drug substance (DS) sameness: 19%

- Toxicology-exposure (Tox-E/L) issues: 20%

- Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) problems: 14%

- Deficiencies flagged during consult: 7%

- Other miscellaneous issues: 20%

These numbers don’t lie. If you’re submitting an ANDA, your biggest risks are impurities, proving your drug substance matches the reference drug, and toxicology data gaps. But the most common single issue? Dissolution problems. About 23.3% of applications fail because their dissolution method doesn’t properly show the drug releases the same way as the brand-name version. That’s more than one in five.

Dissolution: The #1 Pitfall

Dissolution testing is supposed to prove your tablet or capsule breaks down in the body the same way as the original. But too many companies use outdated methods. They stick with Apparatus 2 (the paddle) even when their product is modified-release or has complex coatings. The FDA expects dissolution methods to reflect real-life conditions-pH levels of 1.2, 4.5, and 6.8-and to be validated with discrimination testing. If your method can’t tell the difference between a good batch and a bad one, it’s useless.

One company submitted an ANDA for a modified-release tablet and got a deficiency letter because their dissolution method used a 50 rpm paddle speed, while the reference drug used 75 rpm. The FDA didn’t just ask for a change-they asked for a full re-validation with biorelevant media. That added 11 months to their timeline.

Drug Substance Sameness: More Than Just Chemistry

"DS sameness" means your drug substance (the active ingredient) must be chemically identical to the reference listed drug. But it’s not enough to say "it’s the same molecule." The FDA wants proof that the physical form, particle size, polymorph, and impurity profile match exactly.

For peptides-like insulin or semaglutide generics-the bar is even higher. You need circular dichroism, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, and size-exclusion chromatography to prove the protein folds the same way. One applicant skipped the aggregation profile test because their internal lab didn’t have the equipment. The deficiency letter came back with a 14-month delay while they arranged for third-party testing.

And here’s the kicker: 82% of DS sameness deficiencies come from problems in the Drug Master File (DMF) your supplier submitted. If your API vendor doesn’t have a clean DMF, your ANDA fails-even if your own data is perfect.

Impurities: The Silent Killer

Impurities aren’t just leftovers from manufacturing. They’re potential toxins. The FDA follows ICH Q3 guidelines, and if you’re missing even one impurity study, you’ll get a deficiency letter. The most common failure? Not doing a (Q)SAR analysis for mutagenic impurities under ICH M7. That’s a computational tool to predict if a degradation product could damage DNA. Many small companies skip it because it’s expensive. But the cost of a deficiency letter is worse.

One applicant got a deficiency for an unqualified impurity that made up 0.15% of their product. They thought it was harmless. The FDA required a full toxicology study. The result? A $1.8 million delay and 16 months of lost time. That impurity was never the issue-it was the lack of data proving it was safe.

Why Some Companies Keep Failing

It’s not just about technical errors. It’s about mindset. Companies with fewer than 10 approved ANDAs have deficiency rates 22% higher than those with 50 or more. Why? Experience matters. Established players know what the FDA expects before they even submit. They’ve been through the process. They’ve seen the letters.

Complex products-peptides, modified-release tablets, topical creams-face deficiency rates 40% to 65% higher than simple immediate-release pills. That’s because they’re harder to characterize, harder to manufacture consistently, and harder to prove bioequivalent. The FDA has specialized teams now just for these products, and they’re watching closer than ever.

What You Can Do to Avoid Deficiency Letters

There’s a clear pattern: most deficiencies are preventable. Former FDA director Dr. David Rope said 65% of major issues could be avoided with better preparation. Here’s how:

- Request a pre-ANDA meeting. Companies that do this see deficiency rates 32% lower. You get direct feedback from the FDA before spending millions on testing.

- Validate your dissolution method properly. Use the right apparatus. Test across pH levels. Show it can discriminate between batches.

- Fix your DMF. If your API supplier’s DMF has issues, your application will too. Audit their file before you submit.

- Do the M7 study. Don’t assume your impurities are safe. Prove it.

- Document everything. Applications with detailed development reports have 27% fewer deficiencies. The FDA doesn’t just want data-they want context.

- Use Quality by Design (QbD). Build quality into the process, don’t just test for it at the end.

One company spent $2 million on a generic version of a high-revenue drug. They skipped the pre-meeting. They got a deficiency letter on dissolution, DS sameness, and impurity control-all in one. They had to re-run 18 batches. The total cost? $4.3 million and 21 months. They could’ve avoided all of it with a single 90-minute meeting with the FDA.

The Cost of Delay

Every deficiency letter adds about $1.2 million in costs-testing, re-submission, legal fees, lost revenue. For a $100 million/year drug, a one-year delay means losing $100 million in potential sales. That’s why big companies invest heavily in regulatory teams. Small companies? They often don’t have the budget.

But here’s the good news: the FDA is trying to help. Their "First Cycle Generic Drug Approval Initiative" launched in 2023 and already cut dissolution-related deficiencies by 15%. They’ve released new template responses for the 10 most common deficiency categories. And by Q3 2026, they plan to roll out AI tools that flag submission errors before you even hit send.

Meanwhile, the Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) program gives priority review to certain drugs. Those applications have a 73% first-cycle approval rate-compared to the industry average of 52%.

What’s Next?

The future of generic approvals is clearer, faster, and more predictable. But only for those who prepare. The FDA isn’t making the rules harder-they’re just expecting you to know them. If you’re submitting an ANDA in 2025, you can’t afford to guess. You need data. You need documentation. You need to understand what the FDA is looking for before you send your application.

Deficiency letters aren’t punishment. They’re feedback. And if you treat them that way, you’ll get to market faster, cheaper, and with fewer surprises.

What is a deficiency letter from the FDA?

A deficiency letter is a formal notice from the FDA that identifies specific issues in an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) that prevent approval. It lists technical, scientific, or documentation gaps that must be addressed before the application can move forward. It is not a rejection, but a request for additional information or corrections.

What are the most common reasons for FDA deficiency letters in generic drugs?

The top reasons include dissolution method failures (23.3%), unqualified impurities (20%), drug substance sameness issues (19%), toxicology-exposure concerns (20%), and inadequate control strategies for elemental impurities (13%). Many also stem from poor documentation, outdated testing methods, or problems in the Drug Master File (DMF) provided by the API supplier.

How long does it take to resolve a deficiency letter?

Resolution time varies. Simple clarifications may take 2-4 months. Complex issues-like adding toxicology studies for impurities or re-validating dissolution methods-can take 12 to 18 months. On average, each deficiency adds 6-12 months to the approval timeline, depending on the nature of the issue and how quickly the applicant responds.

Can you avoid deficiency letters entirely?

Yes, many are preventable. Companies that request pre-submission meetings with the FDA, use Quality by Design (QbD) principles, validate methods thoroughly, and audit their suppliers’ Drug Master Files reduce deficiency rates by up to 32%. The FDA estimates that 65% of major deficiencies could be avoided with better preparation and understanding of their expectations.

Why do complex generics have higher deficiency rates?

Complex generics-like peptides, modified-release tablets, and topical products-require more sophisticated testing to prove bioequivalence. Their manufacturing is harder to control, their physical properties (like particle size or crystalline form) are harder to characterize, and their dissolution behavior is more variable. The FDA requires advanced analytical techniques (e.g., circular dichroism, SEC, FTIR) and more extensive data, which many applicants are unprepared to provide.

What’s the difference between a deficiency letter and a complete response letter?

There is no difference. The FDA now uses "deficiency letter" as the standard term for what was previously called a "complete response letter" (CRL) in the generic drug space. Both refer to the same document: a formal notice listing deficiencies that must be resolved before approval.

How does the FDA’s new AI tool help reduce deficiency letters?

The FDA is developing an AI-assisted pre-submission screening tool set to launch in Q3 2026. It will automatically check submissions for common errors-like missing M7 studies, incorrect dissolution apparatus selection, or incomplete DMF references-before the formal review begins. Early tests show it can catch up to 35% of preventable deficiencies, helping applicants fix issues before submission and reducing first-cycle rejection rates.

Do small companies have a harder time avoiding deficiency letters?

Yes. Companies with fewer than 10 approved ANDAs have deficiency rates 22% higher than those with 50 or more. Smaller firms often lack dedicated regulatory teams, access to advanced testing equipment, or experience navigating FDA expectations. They’re also less likely to use pre-submission meetings, which are proven to reduce deficiencies.

Chris Jahmil Ignacio

December 3, 2025 AT 19:53The FDA is just protecting Big Pharma’s profits. They know 90% of these deficiencies are manufactured to delay generics. Why else would they demand absurd tests like circular dichroism for insulin when the molecule is identical? It’s not about safety-it’s about control. And don’t get me started on that AI tool they’re rolling out. That’s just a shiny distraction so they can say they’re modernizing while quietly raising the bar even higher. They’ve been doing this for decades. You think they care about patients? No. They care about revenue streams. And you’re all just sheep following their playbook.

Paul Corcoran

December 4, 2025 AT 01:23Hey everyone-just wanted to say this post is spot on. I’ve been in this game for 15 years and I’ve seen companies waste millions because they treated the FDA like a hurdle instead of a partner. The pre-ANDA meeting? Total game-changer. I had a client who skipped it, got nailed on dissolution, and lost a year. Then they booked the meeting, came back with real data, and got approved in 8 months. It’s not about being perfect-it’s about being prepared. And if you’re a small shop? Find a mentor. Talk to someone who’s been there. You’re not alone.

Colin Mitchell

December 5, 2025 AT 10:26Love this breakdown. I work with a lot of startups and honestly, the biggest mistake I see is thinking ‘we’re just making a copy’ so we can cut corners. But the FDA doesn’t care if it’s generic-they care if it works the same. And if your dissolution method uses a 50 rpm paddle when the brand uses 75? That’s not laziness-that’s a red flag. I always tell my teams: if you wouldn’t bet your reputation on your method, don’t submit it. Also-audit that DMF. Your API vendor’s sloppy paperwork is your problem too. Don’t wait until the letter comes to fix it.

Susan Haboustak

December 6, 2025 AT 19:2423.3% fail on dissolution? Pathetic. That’s not incompetence-that’s negligence. Companies that can’t even get the paddle speed right shouldn’t be allowed near a manufacturing line. And the fact that they’re still using outdated methods? Shows they’re not even trying. I’ve reviewed 12 ANDAs this year. Eight had no QbD documentation. Zero. And they wonder why they get rejected? Wake up. This isn’t rocket science. It’s basic science. And if you can’t do it right, someone else will. The FDA isn’t the enemy. The people submitting these half-baked apps are.

Pooja Surnar

December 7, 2025 AT 05:09lol FDA wants you to use 75 rpm? bro just use 50 and call it a day. who cares if it dissolves slower? the body dont care. and that m7 study? expensive af. just say its safe and move on. i know a guy who did this and got approved in 6 months. they dont even read the papers. they just wanna see your money. DMF? who has time for that? just pay the consultant and say its fine. its all a scam anyway. the brand name drug is just as bad. why you think they charge so much? because they can.

Sandridge Nelia

December 8, 2025 AT 15:42This is so helpful! I’m a regulatory coordinator at a small biotech and I’ve been drowning in ANDA prep. The dissolution section had me terrified-until I found the FDA’s new template responses. Seriously, go check them out. They have examples for modified-release, pH gradients, even biorelevant media. Also, if you’re doing peptides, reach out to the CDER’s specialized review team. They’re actually super responsive if you ask nicely. And yes, the AI tool coming in 2026? I’ve tested the beta. It caught a missing ICH Q3 reference I missed. Saved us 3 weeks. 🙌

Mark Gallagher

December 9, 2025 AT 05:00Let’s be clear: this isn’t about science. It’s about American manufacturing being undermined by foreign suppliers with zero quality standards. The DMF issues? Most come from India and China. The FDA’s just trying to protect U.S. patients from cheap, dangerous generics made in back-alley labs. If you can’t meet U.S. standards, go sell your product somewhere else. We don’t need your subpar chemistry here. And don’t tell me about cost-health isn’t a commodity. If you can’t afford to do it right, don’t do it at all.

Wendy Chiridza

December 10, 2025 AT 17:52One thing no one talks about: documentation. I’ve seen so many companies nail the science but lose because their development reports were a mess. The FDA doesn’t just want data-they want the story behind it. Why did you pick that pH? Why did you drop that impurity? If you can’t explain it in writing, they assume you don’t understand it. I started using a template: objective, method, result, rationale. Simple. Clean. It cut our deficiencies by 40%. And yes, pre-meeting? Do it. Even if you think you’re ready. They’ll find something you missed. Always.